Vincent Hack was born in Todd, Minnesota, and graduated from the University of Wisconsin in 1936 with a B.A. degree in fine arts. He subsequently obtained a masters in fine arts from the same institution. His brother was Stan Hack, longtime Cubs third baseman and manager.

Little is know of Hack's career prior to WWII, other than he taught art for a time and produced portrait paintings, oils, watercolors, pencil sketches, and etchings. In the wake of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Hack enrolled in officer candidate school in December 1941. Upon graduation, Second Lieutenant Hack was stationed in the Camp Robinson medical replacement center in Arkansas, and by June 1942 was promoted to First Lieutenant in the Medical Administrative Corps. At least some of his duties included designing and illustrating Army medical publications. By March 1944, Hack had risen to the level of Captain, and was made chief of the Education Branch, a position which he held until February 1945, when he became assistant to the chief of the newly-formed Health Education Unit. Hack does not appear to have seen combat and, by October 1945, he had been discharged from the Army and had taken a position with the Department of the Interior in Cheyenne, Wyoming.

Civilian life (or else Wyoming) does not seem to have agreed with Hack and in 1947 he had moved his family to Tokyo, where he worked as a medical illustrator for the U.S. Army's Medical Section, General Headquarters, Far East Command until 1951. A June 15, 1953 profile entitled "America's Top Japanese Color Printer" in the Wisconsin Alumnus describes (in likely somewhat exaggerated terms) Hack's efforts to study Japanese woodblock printmaking:

"There’s not one American who has ever become a master craftsmen in the

Ancient Japanese art of color wood-blocking printing. But Major Vincent Hack,

’36, Falls Church, Va., has probably progressed as far toward this goal as any of

his countrymen -- and in another eight years he hopes to attain that high rank,

.

It was back in 1947 that Maj. Hack, a medical artist, arrived in Tokyo. He im-

mediately searched out a wood-block artist, Hiroshi Yoshida. “Teach me,” the

major asked,“to make wood-block color prints.”

Yoshida referred Major Hack to a wood-block cutter, the cutter referred him to a

printer, the printer referred him to another printer. It was, the major realized, the

old run-around. He went back to Yoshida, and after a year of perseverance, won

an offer of help as a result of a favor rendered.

He spent the next six months learning color analysis. A Japanese wood-block

artist analyzes the picture he wishes to reproduce to decide the colors he needs.

He plans one wood-cut for each color. He may plan two woodcuts or 30, gaining

range and subtlety as he increases the number. Then the proper design is pain-

stakingly carved on each block -- each swirl of color is duplicated precisely in

wood. Next, a printer brushes the proper colors by varying the pressure. Some

authorities call the Japanese wood-block the world’s highest developed color

printing.

After Maj. Hack learned color analysis, he still had a long way to go. He located a

master cutter, and by dint of more lengthy persuasion, extracted from him a

promise: “You will be a No. 1 American cutter.”

The master cutter required Maj. Hack to hold an egg against the handle of the cut-

knife. If the egg broke, it proved he was not using a delicate touch. For economy,

the cutter furnished only rotten eggs. After breaking a few, Maj. Hack brought his

own, fresh ones.

Before leaving Japan in 1951, Maj. Hack saw his prints hanging in Japanese

exhibitions. Some Japanese viewers thought they were seeing a new school of

wood-block printing. Maj. Hack explains that he gives the faces of his subjects

more characterization than the Japanese do.

Maj. Hack is now [a Medical Training Aids Officer] with the Armed Forces

Institute of Pathology in Washington. He spends many off-duty hours with his

cherry-wood blocks. It requires about eight months from conception of a

painting to completion of prints.''

A similar profile in The Washington Star Pictorial Magazine in 1952 claimed that Hack knocked on Yoshida's door every week for a year. What finally got him inside Yoshida's doorway to learn color analysis was his assistance in rephrasing proposed advertising for an upcoming woodblock print exhibition into proper English. It also revealed that the woodblock carver who trained him lived on the route between Hack's office and his home. Hack would allegedly drop by the carver's home every other night with a bottle of sake under his arm in order to get the woodblock carver in the proper mood to instruct him.

while colors are flashed on a screen

Later in 1953, Major Hack arrived at Fort Sam Houston's Brooke Army Medical Center (BAMC) in San Antonio, Texas, where he stayed until his retirement with the rank of colonel in 1969. During his tenure at BAMC, Hack served as the Medical Trainings Aids Branch Chief, Officer-in-Charge of the AMEDD Museum, and BAMC's Chief Information Officer.

As early as 1959, Hack was a pioneer in advocating for realistic training for military and civilian preparedness programs using simulated casualties. Although he also conducted research into body language and extrasensory perception, his most important contribution was probably studies on the psychological and therapeutic effects of color on healing, safety, personality, eye fatigue, and subliminal messaging. Hack had obtained a doctorate of philosophy on the psychology of color at Tokyo University in 1951, and went on to become one of the world's foremost authorities on the subject.

An August 1952 profile in Popular Mechanics stated that Hack learned the technique of Japanese woodblock printmaking from both Japanese and Korean craftsmen, the latter presumably occurring during his Army service in the Korean conflict. By the date of the article, Hack was said to have carved more than 150 woodblocks to make 13 woodcuts, noting that as many as 30 blocks were used in one print. Several articles state that two of his artworks are in the permanent collection of the Smithsonian. After some investigation, I was able to indeed confirm that Hack donated copies of his Cho-Cho-San prints to the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History. on June 8, 1951.

Silver Eagle insignia with his wife and daughter looking on

At present, it's unclear if Hack continued to make woodblock prints beyond the mid-1950s. To date, I have only been able to catalogue fourteen woodblock print designs (and have not been able to locate any of his etchings). His prints tend to be undated and most appear to be known only by descriptive titles.

Due to their monochromatic nature, the following three prints are likely some of Hack's earliest efforts in woodblock printmaking.

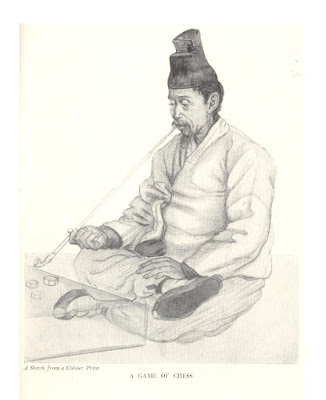

The Korean subject of this next print suggests that it (and perhaps the "Korean Dancing Girl") were made by Hack at some point during the Korean War (c. 1950-1953).

It's difficult to deny that, not only do most of Hack's bijin prints skirt the border of kitsch, but more than few actually go in country on a three-day pass. Certainly Hack had a built-in audience for such prints given the number of lonely servicemen in Japan or Korea during the Occupation of Japan and the Korean Conflict and then, later on, those stateside at Fort San Houston. Nor would I dispute that there have been plenty of other Western woodblock artists, including those that did not study in Japan, with a more developed aesthetic sensibility. So why pay any attention at all to Hack's prints? The answer is that, despite their prosaic natures, they are rare examples of a Western print artist not merely becoming proficient in the rudiments of Japanese woodblock carving and printing, but actually being able to utilize arcane printing techniques that, for the most part, only master printers in Japan were capable of carrying out.

Hack's "Mandarin Duck" print, for example, looks deceptively simple in design.

Although some bokashi appears to have been employed, it was carefully

printed (and overprinted) in black and shades of grey in an effort to introduce shading, and thereby the suggestion of three-dimensional

volume into what is otherwise a flat medium of expression. While his

"Hunting Ducks" print was presumably primarily a carving exercise, it provides an

interesting modern example of a woodblock print made in the style of an

etching, owing more than a little to the waterfowl prints of Felix

Bracquemond.

But it is Hack's figurative prints where he tends to pull out all the stops. The "Korean Smoking" and "Korean? Dancing Girl" prints, for example, have silver mica backgrounds. The "Cho-Cho-San" prints employ metallic pigments with a sprinkling of mica on their kimono sashes and bustles, with silver mica on the front of the fan. Prior to Hack, the only Western printmakers than I can recall who were able to make Japanese style woodblock prints with mica were Prosper-Alphonse Isaac, who learned the technique from Mokuchu (Yoshijiro) Urushibara, and Jules Chadel, who learned it either from Urushibara or Isaac.

Hack uses baren sujizuri to create the background swirls for his "Chinese Bijin and Dragon" print, a technique associated with some of the best bijin prints of Ito Shinsui and Torii Kotondo. Hack make predominant use of the woodblock's grain in the background of "Male Temple Dancer, Bangkok," but what made it create excited comment in Japanese woodblock print circles was the fact that the background block for that print was printed from a block of American pine, rather than traditional Japanese cherrywood. More than forty years would pass before another Western artist, Paul Binnie, would emerge on the woodblock print scene with such a range of printing expertise.

After he retired in 1969, Col. Hack would continue to lecture about the psychology of color until his death in 2001. He is buried at the Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery, next to his wife Joyce, who died twelve years earlier.

If anyone has knowledge of other woodblock print designs by Hack (or better images of the ones I have reproduced above), please get in contact with me at the e-mail address at the top right of this page. If a comment box doesn't appear below, click on this link instead: http://easternimp.blogspot.com/2018/11/hack-jobs.html