Photo of Geoffrey S. Garnier (c. late 1920s?)

Jill Garnier became a painter in oils and watercolors, whereas Geoffrey Garnier devoted himself primarily to etching, engraving, and aquatints. Almost exclusively self-taught, Garnier learned intaglio printing from French manuals, from studying old prints, and from his own experiments in the field whereby he rediscovered old techniques that had been lost over time and made improvements to others that allowed him to increase print production in less time without any concomitant loss in quality. From practically the outset, he was hailed by critics as an "etcher of outstanding ability," producing works of technical complexity that surpassed that found in the works of most other British etchers. Equally at home with landscapes and figurative works, his favorite subjects were Cornish land and seascapes, children, and British naval ships of yore.

St. Mary's, Penzance by Geoffrey S. Garnier

(aquatint)

(aquatint)

Between 1924 and 1931, Garnier produced 228 plates, roughly half of which were blatantly commercial works produced simply to help pay the bills. During that period, Garnier did his own printing, cut his own mounts, and managed his own publicity. With the advent of the Great Depression, however, Garnier, like most etchers, found it increasingly difficult to make a living from his art. In an attempt to increase sales while simultaneously relieving himself of the pressures of marketing, Garnier signed a three-year contract with the London-based publisher and dealer Arthur Greatorex Ltd.

The End of the Chase by Geoffrey S. Garnier

(aquatint)

It was Greatorex who suggested that Garnier tackle oriental subjects as a means of generating sales. Greatorex had experienced considerable success marketing the Asian art deco prints of the American etcher Dorsey Potter Tyson, prints that recently had become prohibitively expensive for Greatorex to sell due to a fifty percent import duty levied in Great Britain. Consequently, Greatorex was hoping to groom Garnier as a suitable replacement for Tyson.

Greatorex sent Garnier books, views of Japan, and travel magazines for inspiration, as well as an etching by Tyson as an example of the type of print it was looking for. Garnier asked for a second copy of the Tyson etching so that he could compare them and work out how they had been produced (a technique that effectively combined the printing of a normal etching simultaneously with that of printing a monotype). To achieve the bright colors of Tyson's prints, Garnier used opaque colors that deeply impregnated a very absorbent type of Japanese paper that Garnier had specially selected for such prints.

Old Molesworthy Mill by Geoffrey S. Garnier

Courtesy of Hatfield Hines Gallery

(aquatint)

Courtesy of Hatfield Hines Gallery

(aquatint)

Greatorex sent Garnier books, views of Japan, and travel magazines for inspiration, as well as an etching by Tyson as an example of the type of print it was looking for. Garnier asked for a second copy of the Tyson etching so that he could compare them and work out how they had been produced (a technique that effectively combined the printing of a normal etching simultaneously with that of printing a monotype). To achieve the bright colors of Tyson's prints, Garnier used opaque colors that deeply impregnated a very absorbent type of Japanese paper that Garnier had specially selected for such prints.

The Wish Bone by Geoffrey S. Garnier

(aquatint)

Greatorex was very hands on, making specific requests for changes in Garnier's proofs to which Garnier acquiesced. Although Queen Mary

acquired copies of A Song of Old Cathay and The Garden God, business overall was slow. The only print Greatorex was selling in any quantity was The Sand Cart, Garnier's most popular print that pre-dated Garnier's association with Greatorex. (By the 1930s, Garnier had sold nearly 3000 copies of that particular design.) Garnier also bemoaned the fact that he would spend a week printing a batch of proofs but not be paid for them by Greatorex for a year or more. Unable to negotiate a prompter payment schedule on financially acceptable terms, Garnier terminated his relationship with Greatorex before the end of the contract term and reverted back to self-publishing his own work.

The Sand Cart by Geoffrey S. Garnier

(aquatint)

(aquatint)

I have been able to catalog at least 10 Asian-themed prints by Garnier, all of which appear to have been produced circa 1931-1933. Many of these prints employ titles and/or monograms written from top to bottom, disguised to look more like Chinese characters than Roman alphabets in an attempt to reinforce and complement the exotic Far-Eastern nature of the subjects depicted. Garnier's debt to Tyson is palpable, especially in his prints of children and sampans. While I am not a great fan of Tyson's work, to my eyes Garnier's prints come across as rather banal and jejune in comparison. Garnier himself acknowledged that they were mere potboilers and thought little of them or the "blighters" who bought such "trip[e]."

The Little Ginger Seller was said to have been produced in an edition of one hundred, but I have found no information about print edition size for Garnier's other prints. It is possible that they were issued with edition labels similar to those sometimes found with Tyson's prints, but that remains a speculative hypothesis until such a label actually turns up. Collectors, however, should be aware that there are also cheap, posthumously-issued "restrike etchings" readily available today in the marketplaces. I have not had an opportunity to view such things in person, but I suspect that they are printed on very different paper and that they are not actually etchings at all but rather lithographic reproductions. In all known cases, they use different colors than those found in Garnier's original prints and often omit certain details altogether.

The Little Ginger Seller by Geoffrey S. Garnier

Size: 17.8 cm x 12.4 cm

(L: colored aquatint; R: restrike etching)

Size: 17.8 cm x 12.4 cm

(L: colored aquatint; R: restrike etching)

The Little Ginger Seller by Geoffrey S. Garnier

Size: 17.8

cm x 12.4 cm

(L: colored aquatint variant; R: alternate state aquatint)

A

Fish from Hwant Ho by Geoffrey S. Garnier

Size: 36.8

cm x 28.6 cm

(L: colored aquatint; R: restrike etching)

The Good Companions by Geoffrey S. Garnier

Size: 27.3 cm x 18.8 cm

Size: 27.3 cm x 18.8 cm

(L: colored aquatint; R: restrike etching)

China Seas by Geoffrey S. Garnier

Size: 26.5 cm x 30.3 cm

(L: colored aquatint; R: colored aquatint variant)

Size: 26.5 cm x 30.3 cm

(L: colored aquatint; R: colored aquatint variant)

The Bird Charmer by Geoffrey S. Garnier

Size: 17.8 cm x 12.4 cm

(L: colored aquatint; R: restrike etching)

Size: 17.8 cm x 12.4 cm

(L: colored aquatint; R: restrike etching)

Note: I have come across a reference to a Garnier print described as a girl selling finches, which probably refers to this design.

The Blue Umbrella by Geoffrey S. Garnier

Size: 17.8 cm x 13.3 cm

Size: 17.8 cm x 13.3 cm

(L: colored aquatint; R: restrike etching)

Night by a Tropical Sea by Geoffrey S. Garnier

Size: 28 cm x 22 cm

Size: 28 cm x 22 cm

(colored aquatint)

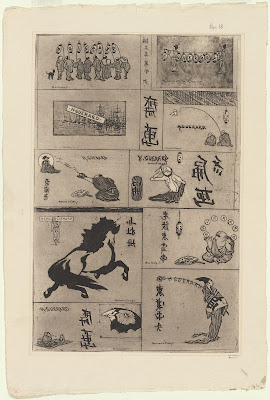

A Song of Old Cathay by Geoffrey S. Garnier

Size: 26 cm x 18 cm

Size: 26 cm x 18 cm

(L: colored aquatint; R: restrike etching)

The Hour of Evening Rice by Geoffrey S. Garnier

Size: 28.1 x 24.3 cm

Size: 28.1 x 24.3 cm

(L: colored aquatint, courtesy of the Josef Lebovic Gallery; R: colored aquatint variant)

The Garden God by Geoffrey S. Garnier

Size: 27

cm x 19 cm

(L: colored aquatint; R: restrike etching)

The Garden God by Geoffrey S. Garnier

Size: 27

cm x 19 cm

(colored aquatint variant)

Note: "The Garden God" is sometimes erroneously referred to by dealers as "The Golden God." I have come across a reference to a Garnier print called "Buddha," which possibly also refers to this same design.

[Lady with Fan] by Geoffrey S. Garnier

Size: 18 cm x 13 cm

Size: 18 cm x 13 cm

(restrike etching)

In addition, I should add that the Bushey Museum has a plate which its records call "Japanese Water Carrier." Whether this is an inscription on the plate or just a descriptive title for the image in the plate is not known at this time. It is also possible that it is the actual plate for "The Little Ginger Seller" print with the cataloger confusing a ginger jar for a water jar.

Photo of Geoffrey Sneyd Garnier (c. 1936)

If anyone has any additional information about Garnier's Asian aquatints, or additional images of same to contribute to this blog, please let me know. For more information about the life and career of Geoffrey Garnier, I recommend Geoffrey and Jill Garnier: A Marriage of the Arts by John Branfield (Sansom & Company 2010).

If a comment box does not appear below, click on this link instead: http://easternimp.blogspot.com/2017/04/asian-art-deco-2-geoffrey-sneyd-garnier.html