Nouët's own inclinations were originally more of the literary, rather than artistic, variety. From the age of twelve, Nouët dreamed of becoming poet and, at Lycée Saint-Grégoire in Pithiviers, he regularly composed verses and began to read the poetical revues of the day. After high school, he continued his literary studies at the Sorbonne in Paris. By 1910, he was living in Montmartre, working at the publishing house Renaissance du Livre, and composing a poem a day, some of which appear in the revue L'hermitage under his newly-adopted pen name "Noël Nouët." Nouët became friends with the writer Charles Vildrac, who introduced him to Parisian literary circles. His first collection of poems was published that year under the title Les Étoiles entre les feuilles, for which he won the inaugural Prix de littérature spiritualiste. Two more poetry collections followed in 1912 and 1913.

Tokyo: Old City, Modern Capital, Fifty Sketches (1937)

The outbreak of World War I, however, temporarily put Nouët's literary career on hold. He enlisted in the army in a manner that allowed him to serve without being posted to the front. After the war, Nouët became at regular at Parisian literary salons where he met the painter and print designer Hakutei Ishii, the poet Akiko Yosano, her poet husband Tekkan Yosano, and the poet Yaso Saijô, all of whom became his friends when he later lives in Japan. Nouët married in 1920, but found himself suddenly widowed and was consumed by grief for several years. In 1925, he decided to apply for a three-year position as a French teacher at Shizuoka High School near Mount Fuji. He left Paris in January 1926 with his new wife Yvonne, and arrived in Yokohama on March 13, 1926. In addition to teaching the French language and literature in Shizuoka, he also taught a course once a week at the Military Academy in Tokyo, using those weekly trips to explore the historical sites of the capital on foot. He also published in Japan a book in French entitled Paris depuis deux mille ans.

Nouët and his wife returned to France in March 1929 via the Trans-Siberian railway. He resumed his poetry career, supporting himself by teaching French to the Japanese of Paris. In 1930, his fourth collection of poems was published, many of which describe the Japanese landscape. That same year, the Japanese ambassador in Paris offers him a three-year renewable position as a professor of French at the Tokyo School of Foreign Languages (later the National University of Foreign Languages) in Hitotsubashi. Evidently Japan did not suit Yvonne Nouët; the pair separates and Noël Nouët travels to Tokyo alone.

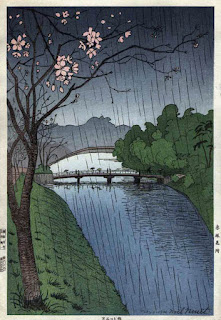

Between classes at the Tokyo School, Nouët strolls through the streets of Kanda and Ginza. Eschewing Hakutei's recommendation to use a pencil, Nouët begins to make ink pen sketches of the city's sights. Inspired by Hiroshige's Tokyo prints, he seeks out aerial views of city drawn from the top of the Tokyo hills, building terraces, and bridges. Nouët is also drawn to scenes in which remnants of Edo are contrasted with modern buildings and monuments of present-day Tokyo. His first sketches appear in the monthly magazine for French students La Semeuse (later called La France), and then in a postcard series called Tokyo Ancien et Moderne. The president of The Japan Times, Hitoshi Ashida, then commissions him to produce a weekly sketch for the Sunday edition. After three years, The Japan Times and Mail publishes a collection of fifty of such sketches in a book entitled Tokyo As Seen By A Foreigner (1934). The collection includes a brief history of Tokyo by Nouët with comments on each sketch in both French and English.

This collection is well-received and a second volume of an additional fifty sketches is published the following year. In 1937, a third collection entitled Tokyo: Old City, Modern Capital, Fifty Sketches is published by La Maison Franco-Japonaise with a preface by the Viscount Sukekouni Soga.

Nouët both created new designs for this series and reworked early sketches in greater detail. These color prints appeared at a rate of two a month, sometimes requiring two to three weeks to carve and between 12 to 20 separate printings. There is, however, a suggestion in certain quarters that zinc plates may have been used for the color blocks or even to produce the keyblock. As a result of this series, Nouët's friends begin to refer to him as Hiroshige IV. Collectors should also know that multiple editions of Nouët's prints have been printed by Doi Hangaten and its successor companies over the years, not only before and after WWII, but also after Nouët's death. To determine the approximate time period when a specific copy was printed, I suggest that collectors consult this article, this article, and/or this article.

The outbreak of the Second World War created certain difficulties for a Frenchman residing in Japan. Nouët continued to teach French to interested students, but he was obliged to compose his own French textbooks since French imports were banned. He also somehow managed to publish during wartime an essay and sketch collection about Japanese scenery, Nihon fūbutsu-shi, which is notable because it includes images outside of Tokyo, such as Kinukawa, Lake Kawaguchi, the Japanese mountains, and even the Summer Palace in Peking.

The American bombing of Tokyo in 1944 resulted in a suspension of his classes, and Nouët's house in Fujimicho, in the district of Kojimachi, was destroyed in an air raid on March 10, 1945. By that time, however, Nouët had been forcibly moved to Karuizawa and placed under house arrest along with such countrymen as the journalist Robert Guillain and the artist Paul Jacoulet.

Nouët returned in October 1945 to a Tokyo occupied by the American forces. The following year, he published a rueful collection of fifty sketches which either depicted Tokyo in ruins or else largely documented for posterity sites that sadly no longer existed after the war. A revised version was subsequently issued in 1948 but with new sketches replacing those scenes showing the devastation of Tokyo.

After the war, Nouët originally settled in Kanda, but the distance from his workplace to the new location for Tokyo School of Foreign Languages eventually made him decide to resign his teaching post. He soon found work at the University of Tokyo, Waseda, Gakushuin, the French Athenaeum, and then, in 1952, at the Franco-Japanese Institute of Tokyo. In 1947, the French government awarded him the Legion of Honor. Also in 1947, the Tokyo Shuppansha Publishing House published a new collection of sketches entitled Autour du Palais Impérial.

In 1954, Hosei University published a Japanese translation of Nouët's Silhouettes de Tokyo, a book describing the old and the new Tokyo through poems, essays, and sketches with one chapter devoted entirely to Hiroshige. The following year, the Asahi Shinbun newspaper published a Japanese translation of Nouët 's Histoire de Tokyo. (The original French version was eventually published in 1961, although an English version would not appear until 1990 under the new title The Shogun's City.)

In 1956, the Japanese government decorated Nouët with the Zuihosho Medal, the Order of the Sacred Treasure, Fourth Class, for his contribution in the field of education and his efforts to introduce Japan history and culture abroad. In 1957, Nouët presented his dissertation on Edmond de Goncourt and the Japanese arts at the University of Tokyo, for which he obtained the title of Doctor of Letters.

During the summer of 1957, Nouët returned to France for three months. In 1962, he decided to leave Japan after spending nearly thirty-five years of his life there. In 1965, the city of Tokyo bestowed upon him the rare honorific title of "Citizen of Tokyo." Back in Paris, Nouët resumed his marriage with Yvonne, and the two lived together until his death in 1969.

Courtesy of the Ukiyoe-Gallery

Having acquired many of Nouët's books, I have been able to spot many drawings that clearly were progenitors for most of the print designs published by Doi. I thought it might be illuminating to display them and let my readers discern the changes, sometimes big, sometimes small, that occurred when the drawings were transformed into woodblock prints. In some cases, no generally corresponding drawing could be readily located, and I have used the closest related Nouët drawing of the same subject I could find (if any), even it the drawing was created after the print had been made and therefore could not have inspired the print.

Courtesy of Hanga.com

Note: See also the cover for Silhouettes de Tokyo (1954) shown above.

Courtesy of the Ukiyoe-Gallery

Courtesy of Peter Pantzer

Nihonbashi (1936) woodblock print

Courtesy of Hanga.com

Courtesy of the Ukiyoe-Gallery

Courtesy of the Ukiyoe-Gallery

Kagurazaka (1937) woodblock print

Courtesy of Artelino.com

At least one Doi house artist, Tsuchiya Koitsu, appears to have been influenced by Nouët's woodblock prints. How else can one explain the similarity between Nouët's Kagurazaka print and the one that Koitsu designed two years later?

The above 24 prints by Nouët formed the series Tokyo fukkei zen nijuyon mai (Scenes of Tokyo, Twenty-Four Views) which Doi Hangaten published in 1937. To date, I am aware of four other prints designed by Nouët outside of that series:

Postscript: About a month after posting this essay, I saw this Nouët drawing of Nijubashi put up for auction. Unfortunately, the opening bid price was 1.8 million yen. At that price, I'll just have to go without. :)