Portrait of Henri Guérard at the press (1888) by Henri-Charles Guérard

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

(drypoint)

Henri Guérard at his press (1888) by Henri-Charles Guérard

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

(etching with aquatint and roulette)

Posthumously printed from an unpublished plate by A. Porcabeuf

and published in Gazette des Beaux-Arts, Vol. 37 (1907)

Courtesy of Idbury Prints

(etching)

With the death in 1880 of Jules Jacquemart, Guérard replaced him as the

leading reproductive print artist of the time. Guérard also printed the

etchings of other artists, such as those by Félix Buhot and his close

friend Édouard Manet (whose favorite pupil, Eva Gonzalès, became Guérard's first wife).

The Boy with Soap Bubbles (1868-69) by Édouard Manet

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

(etching printed by Henri-Charles Guérard)

Title Page for the Japonisme portfolio (1885) by Félix Buhot

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

(etching in sanguine printed by Henri-Charles Guérard)

But Guérard was more than just a professional printer; he was also an original and innovative etcher in his own right. Guérard would experiment with different types of paper, inks, and printing effects to improve or vary his images. In "La Rue Chevert," for example, Guérard removed small amounts of paper pulp to pockmark the sheet to transform a cityscape into a winter scene and mounted the resulting print on Japanese paper speckled with gold to enhance the effect of the snow.

La Rue Chevert (pre-1888) by Henri-Charles Guérard

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

(etchings with aquatint)

Inspired by the efforts of August Lepère, Guérard also made tentative forays in to woodblock printing near the end of his life. As in the contemporaneous woodblock prints of Arthur Wesley Dow, Guérard would print the same design in varying colors to reflect the time of the day or simply to project a different mood. In "Soleil couchant, Honfleur," for example, he would add a moon printed in white ink whose light casts a reflection in the harbor water below, anticipating similar effects in the prints of Kawase Hasui and Hiroshi Yoshida over two decades later. Guérard's prints, however, rely upon much larger areas of flat color (and overall were of much larger size) than in the prints of Dow.

Soleil couchant, Honfleur (c. 1895) by Henri-Charles Guérard

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

(left: woodcut printed in black; right: colored woodcut)

Soleil couchant, Honfleur (c. 1895) by Henri-Charles Guérard

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

(colored woodcut)

Of all the French etchers, none embraced the Japonisme movement more fervently than Guérard. I'm not quite sure exactly when the Japanese bug bit him, but he certainly was firmly under its spell by 1883, the date that Louis Gonse published L'Art japonais. Guérard contributed more than 200 designs of Japanese subjects to this seminal work.

Porte-bouquet et crabe (1882) by Henri-Charles Guérard

[also used in L'Art japonais (1883)]

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

(color etching with roulette)

Philippe Burty (c. late 1880s) by Henri-Charles Guérard

It is also known that Guérard was well-acquainted with Philippe Burty, the French art critic, Japanese art collector, frequent contributor to Paris à l'eau-forte, and

coiner of the term "Japonisme." Burty, an enthusiastic patron of Guérard's work, was a particular champion of Hokusai, and no doubt

exposed Guérard early on to Hokusai's oeuvre.

Posthumously printed from an unpublished plate by A. Porcabeuf

and published in Gazette des Beaux-Arts, Vol. 37 (1907)

Courtesy of Idbury Prints

(etching)

In Hokusai, Guérard found both inspiration and a shared sense of humor that was reflected in many of his mature prints. For example, the following print of Japanese men playing a board game was directly inspired by a drawing in one of the volumes of Hokusai's Manga. The three central figures are reversed, a not-uncommon result if a design is copied directly onto the plate. Guérard, however, adds two flanking figures of his own while otherwise simplifying the overall design. Although Hokusai's players appear to be playing a game of shogi, Guerard's men are using something more akin to a chess board.

Five figures seated around a board game and a fan (1882) by Henri-Charles Guérard

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

Close-up of a page from the Hokusai Manga, Vol. VIII (1819) by Katsushika Hokusai

Courtesy of the British Museum

(woodblock print)

Guérard's sense of Gallic whimsy is particularly evident in his famous "Assault of the Shoe" print. Here, Guérard appropriates Hokusai's motif of blind men attempting to scale an elephant and turns it into a fantastical comic romp with not-so-veiled erotic overtones. (A version in yellow also exists, but the pink is particularly suggestive.)

L'Assaut du soulier (1888) by Henri-Charles Guérard

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

(color etching with roulette)

Blind Men with an Elephant (1819)

from Hokusai Manga, Vol. VIII by Katsushika Hokusai

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

(woodblock print)

Blind Men with an Elephant (1819)

from Hokusai Manga, Vol. VIII by Katsushika Hokusai

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

(woodblock print)

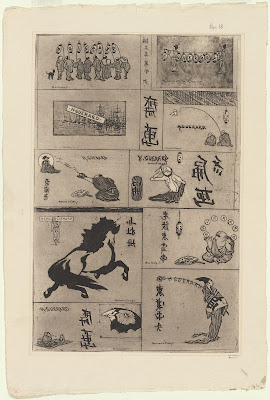

A characteristic of the Manga was Hokusai's multiple depictions on a single page of subjects (be they figures, animals, plants, or objects) sketched at various angles or in various poses. Guérard utilize this format for a number of prints, such as in these etchings of his dog Azor and a series of possibly Manet-inspired black cats.

Azor (Hokusai Manga style) (1888) by Henri-Charles Guérard

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

(color etching)

Sept chats noirs (1888) by Henri-Charles Guérard

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

(drypoint with aquatint)

Two pages from Hokusai Manga, Vol. IX (c. 1814) by Katsushika Hokusai

Courtesy of the British Museum

(woodblock prints)

Guérard also made a number of etchings focusing on a single carved Japanese mask, as opposed to depicting an arrays of such masks as featured in the Hokusai Manga.

Masque Grotesque (pre-1888) by Henri-Charles Guérard

Courtesy of Armstrong Fine Art

(left: cut-out etching printed in green; right: negative proof etching)

Two pages from Hokusai Manga, Vol. II (c. 1814) by Katsushika Hokusai

Courtesy of Arts and Designs of Japan

(woodblock prints)

In other cases, Japanese imagery was appropriated by Guérard simply because it was exotic or fashionably chic, adorning calendars, menus, business cards, and the like for people who traveled in the same circles as Burty, Gonse, Edmond de Goncourt, and Siegfried Bing.

Calendar (1884) by Henri-Charles Guérard

Personal Collection

(etching with drypoint) (intermediate state without dates)

Calendar (1884) by Henri-Charles Guérard

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

(etching with drypoint) (final state)

Japonais sur un encrier (1881) by Henri-Charles Guérard

Courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Art

(etching with drypoint)

Business cards - Japanese subjects (1885) by Henri-Charles Guérard

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

(etching counterproof)

Fifteen uncut blank cards (c. 1880s) by Henri-Charles Guérard

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

(etching with roulette)

After the "Assault on the Shoe," my favorite Guérard etching is probably "Le rat prédicateur."

Le rat prédicateur (c. 1880s) by Henri-Charles Guérard

Courtesy of the New York Public Library

(color etching with aquatint)

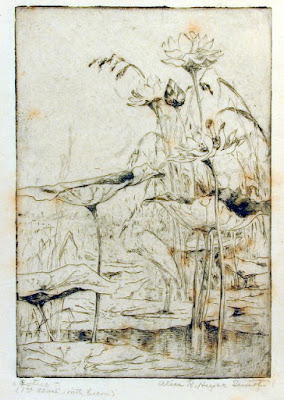

Before winding up this post, I would be remiss if I didn't mention that Guérard, more than any other European artist of the period, was the greatest proponent of the use of the Japanese fan shape in decorative art. Some of his etchings were made in the fan shape, and Guérard also created a number of unique fan paintings.

Fan with mice (c. 1885) by Henri-Charles Guérard

Courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Art

(etching with aquatint)

Shadow Theatre Fan (1885) by Henri-Charles Guérard

Courtesy of the Zimmerli Art Museum of Rutgers Univerity

(brush and ink on printed textile)

Untitled [Magpie] (c. 1890) by Henri-Charles Guérard

Courtesy of John and Lucy Buchanan

(watercolor on silk)

My thanks to Madeleine Viljoen, whose recently-concluded exhibition "A

Curious Hand: The Prints of Henri-Charles Guérard 1846-1897" at the New

York Public Library inspired this post.

Self-Portrait Preparing an Etching (c. 1890) by Henri-Charles Guérard

Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

(line etching with roulette and mezzotint)

If a comment box does not appear below, click on this link instead: http://easternimp.blogspot.com/2017/02/enthralled-with-japan-prints-of-henri.html