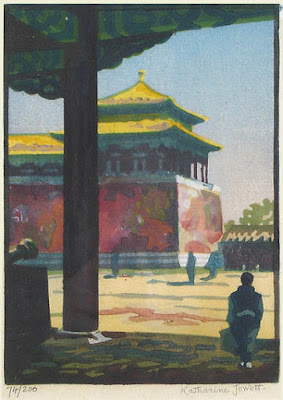

[Japanese Cherry Trees] by Andrew Kay Womrath

Courtesy of the Galerie Michel Cabotse

(woodblock print)

Womrath's works are arguably beyond the scope of this blog. I'm not aware that he ever traveled to the Far East, and, with one arguable exception (the Japanese cherry tree print shown above), he does not seem to have depicted Asian imagery in his prints. He is of interest to me solely because of the fact that Urushibara carved and printed some of his prints.

Salon des Cent (1897) by Andrew Kay Womrath

Courtesy of the Colletti Gallery

(lithographic poster)

Information about Andrew Kay Womrath on the Internet is scarce. Womrath was born in Frankford, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Philadelphia, in 1869. He seems to have first traveled to Europe in the 1890s, where he made contact with representatives of the Arts & Crafts movement in London and Scotland. One of his earliest known works is a series of engravings for Patrick Geddes, editor of the quarterly The Evergreen (Edinburgh). In Paris, he supplied illustrations to the art magazine La Plume, exhibited prints, bookplates, and drawings at the Salon de Champ de Mars in April 1896, and designed a highly regarded poster for the Salon des Cents in 1897, which also exhibited his work.

[Venice Boats] by Andrew Kay Womrath

(woodblock print)

[Venice Boat] by Andrew Kay Womrath

(woodblock print)

For the rest of this life, Womrath continued to sail between France, Great Britain, and the United States (though, as many of his prints evidence, he clearly spent some time in Venice as well). As a pictorial artist, his engravings and drawings were regularly published in such publications as The Savoy, Saint-Nicolas, La Revue du Touring-Club de France, and The Studio (1899-1900), among others. As a metal artist, he participated in the Arts and Crafts Exhibition in Syracuse, New York, in 1903.

[Venice From the Water] by Andrew Kay Womrath

(woodblock print)

[Venice Boats] by Andrew Kay Womrath

(woodblock print)

In the early 1910s, Womrath co-founded Womrath Brothers & Co., a firm of architecture and interior design in New York City. He was a member of the Architectural League, and his work appeared in the annual exhibition of the American Fine Arts Society in1920. Shortly before his death, Womrath's engravings were exhibited at the Grand Palais in Paris in June 1939 as part of the Salon of the Colonial Society of French Artists.

L: Anemones in Vase

R: Anemones in Vase [with Black Background]

by Andrew Kay Womrath

Courtesy of Hilary Chapman Fine Prints

(woodblock prints)

[Canal Scene, Venice] by Andrew Kay Womrath

Courtesy of Hilary Chapman Fine Prints

(woodblock print)

I have not been able to determine as yet when Womrath first attempted to make woodblock prints in the Japanese manner, or if such attempts preceded his studies with Urushibara. In fact, it is not even clear how or when Womrath first came into contact with Urushibara. However, given Womrath's Arts and Crafts background, it would not be surprising to learn that he was on social terms with Frank Brangwyn, and Brangwyn would have been the logical person to have recommend that Womrath study woodblock printing and carving with Urushibara during one of his London stays. If so, Womrath's woodblock prints were likely made sometime between the two World Wars, most likely sometime during in the 1920s.

[The Bridge], #9/45 by Andrew Kay Womrath

Courtesy of the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

(woodblock print)

Urushibara had two of Womrath's prints in his personal possession, which he subsequently donated to the British Museum. Wikipedia asserts that Urushibara purchased these prints from Womrath, but I suspect that they were merely gifts from the student to the master. Of course, another reason why they might have been in Urushibara's possession is because Urushibara may have assisted Womrath with either the carving or printing of these prints.

Magnolia, #6/35 by Andrew Kay Womrath

ex. collection of Yoshijiro Urushibara

Courtesy of the British Museum

(woodblock print)

[...] Brittany, #20/35 by Andrew Kay Womrath

ex. collection of Yoshijiro Urushibara

Courtesy of the British Museum

(woodblock print)

The previously known Womrath collaboration with Urushibara is catalogued as "Canal Scene" (aka Venice by Day) (OS43). While no edition was noted in the catalogue raisonné, the copy below is from an edition of 50. What was not previously known was that a night version of the scene also exists in an edition of 50. While this version is not signed by Urushibara, it is a practical certainty that Urushibara was involved, since the print would have reused the keyblock and most or all of the color blocks that Urushibara would have carved for the day version. A visual comparison of the two prints leaves no doubt in my mind that they were printed by the same person, and that that person was Urushibara.

[Venice by Day], #24 /50 by Andrew Kay Womrath and Yoshijiro Urushibara

Personal Collection

(woodblock print)

[Venice at Night], #1/50 by Andrew Kay Womrath and Yoshijiro Urushibara (unsigned)

Personal Collection

(woodblock print)

In the last few months, a slew of Womrath prints have been popping up for sale directly or indirectly from a representative of the Womrath estate. This next print illustrates the folly of relying solely upon the absence of Urushibara's signature to disprove Urushibara's involvement. The numbered version shown below is signed by both Womrath and Urushibara. However, #43/50 (not shown), however, is signed by neither Womrath nor Urushibara.

by Andrew Kay Womrath and Yoshijiro Urushibara

Personal Collection

Personal Collection

(woodblock print)

The above design is also very similar to another Womrath nocturne print which is not signed by Urushibara. Given this is the only copy I have been able to find, I am not yet willing to rule out the possibility that Urushibara was also involved with this print.

[Trees by Water at Night], #16/30 by Andrew Kay Womrath

Courtesy of Steven Thomas, Inc.

Courtesy of Steven Thomas, Inc.

(woodblock print)

Finally, there is this unnumbered print of a fishing boat that is signed by Urushibara. This copy, like all the other copies I have seen, is not signed by Womrath or numbered. However, it does contains the initials "KW" for "Kay Womrath" printed in the image, the only Womrath copy I've seen to do that so far.

[Fishing Boat] by Andrew Kay Womrath and Yoshijiro Urushibara

Personal Collection

(woodblock print)

The Womrath estate also had this set of prints of a European couple, neither of which is signed by Urushibara. If Urushibara was involved, the absence of his signature was hardly an aberrant oversight, as it appears to be missing from the entire edition. However, the waviness of the right borders of the prints suggest to me that they were carved by Womrath himself. I cannot believe that a professional carver such as Urushibara would have been responsible for such sloppy carving. (If a reader has seen a copy signed by Urushibara, I would be very interested to know about that, as I would about any additional information that confirms or refutes the assumptions I have made in this post about Womrath's prints.)

[European Couple by Day], #5/25 by Andrew Kay Womrath

Courtesy of Arts and Designs of Japan

(woodblock print)

[European Couple at Night], #17/25 by Andrew Kay Womrath

Courtesy of Arts and Designs of Japan

(woodblock print)

It is hard to tell from the following image, but Womrath's Notre Dame print suffers from a small error in registration of the blocks down along the borders of the image, persuasive evidence that it was also printed by Womrath himself and not by Urushibara. Womrath, however, might have been inspired by one of Urushibara's more sophisticated treatments of the same subject.

[Fishermen on the Seine, Paris] by Andrew Kay Womrath

Courtesy of Hilary Chapman Fine Prints

(woodblock prints)

Paris, Notre Dame, Evening by Yoshijiro Urushibara

Personal Collection

(woodblock print)

I think it safe to say that Womrath's prints shown above that include depictions of cloud formations would seem to be among his most mature woodblock prints. Unless Urushibara was involved in the carving or printing of those prints as well, it is apparent that Womrath eventually became a competent woodblock print artist. Nonetheless, while his best prints are not without charm, I doubt anyone would confuse Womrath with any of the major Anglo-English woodblock printmakers of the day.

Gravestone for Andrew Kay Womrath and Georgina Howells Womrath, Biot, France

Courtesy of Keiko Courdy

One final note: Wikipedia and certain other authorities erroneously cite 1869 as the year of Womrath's birth and 1939 as the year of Womrath's death. One of my readers, however, the media artist and documentary film director Keiko Courdy, wrote me to say that she is living in Womrath's former home in Biot, a little village in the south of France between Nice and Cannes. Womrath evidently bought the house in 1920s, and redecorated it with elements from his beloved Venice. His library included books on woodblock printing by Allen W. Seaby, Maurice Busset, Morin-Jean, and Hiroshi Yoshida. Womrath lived there intermittently until his death in 1953. He apparently left Biot in 1943 when the German army invaded the South of France, but returned once the war was over. People in the village remember Womrath as an American painter who was well-liked and very helpful to people in the community. Womrath's ashes (and those of his wife, who died the previous year) are buried in a Biot village cemetery.