Alice Ravenel Huger Smith (circa 1900?)

Courtesy of sticksandstones

(photograph)

Smith was born into a prominent, once-wealthy Charleston family left in genteel poverty in the wake of the Civil War. Other than some basic art training in classes held by the Carolina Art Association, she was essentially self-taught. The Tonalist painter Birge Harrison, who used space on the Smith family's property to paint, was an early influence on Smith even though he declined to provide her with any formal instruction.

Sunday Morning at the Great House (c. 1935) from the series

A Carolina Rice Plantation of the Fifties by Alice Ravenel Huger Smith

Courtesy of the Gibbes Museum of Art

(watercolor)

Although she rarely traveled and never ventured abroad, Smith's work owes a tremendous debt to Japanese art. Her friend and distant cousin was Motte Alston Read, a Harvard professor who retired for health reasons and moved to Charleston. Read had assembled a distinguished collection of Japanese woodblock prints ranging from the black and white prints of the Primitive School to color masterpieces by the likes of Sharaku, Utamaro, Hokusai, and Hiroshige. Read also had an extensive reference library on Oriental art, leading Smith to read such works as Ernest Fenollosa's Epochs of Japanese and Chinese Art. Smith made an intensive study of the prints in Read's collection and created a handwritten catalog listing for each one. Read's collection also included actual ukiyo-e woodblocks, which allowed Smith through trial and error the opportunity to learn how to print colored woodblock prints.

Abe no Nakamaro (1833), from the series A True Mirror of

Chinese and Japanese Poetry

(aka Imagery of

the Poets) by Katsushika Hokusai

Courtesy of the Gibbes Museum of Art (from the Collection of Motte Alston Read)

(colored woodblock print)

The academic exercise of reprinting Japanese prints whetted Smith's appetite to carve and print woodblock prints of her own design. According to Helen Hyde, who spent the winter of 1916-17 in Charleston and became her mentor and friend, Smith's first print was made sometime prior to May 1917. Along with Bertha Jaques, President of the Chicago Society of Etchers, Hyde would provide Smith with technical advice and help her procure blocks of cherry wood and special Japanese paper to be used in her printing and carving efforts. Over the next couple of years, Smith would produce five remarkable woodblock prints depicting Carolina Lowcountry scenes that, for my money, are more Japanese in character than any color woodblock prints made by any foreign print artist prior to the advent of Paul Binnie. Only the prints of B.J.O. Norfeldt come close in my opinion. Indeed, Jaques would write to Smith: "We surrender - both Helen Hyde and myself! You have beaten us at our own game."

Alice Ravenel Huger Smith (c. 1915?)

Courtesy of the Charleston Museum

(photograph)

One of Smith's earliest woodblock prints is "Celestial Figs." Commentators have compared this design to Hiroshige's vertical bird-and-flower prints or one of the Kimpaen gafu ehon designs by Kawamura Bumpo. To me, however, it immediately summons to mind Camille Martin's lithographic cover for L'Estampe Originale, which in turn appears to have been influenced by prints such as those found in Utamaro's Picture Book of Insects or Hokusai's Squirrel on Vine.

Celestial Figs (1917) by Alice Ravenel Huger Smith

Courtesy of the Gibbes Museum of Art

(colored woodblock print)

Cover to Album V of L'Estampe Originale (1894) by Camille Martin

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

(lithograph)

Grasshopper and Cicada (1788) from the

Picture Book of Insects (Ehon mushi erami) by Kitagawa Utamaro

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

(colored woodblock print)

Squirrel on Vine (1830s?) by Katsushika Hokusai

Courtesy of the Ronin Gallery

(colored woodblock print)

Another early Smith woodblock print is "Moon, Flower and Hawk Moth." Commentators have noted the similarity between this print and Hokusai's "Bat and Moon" print since both designs feature a large moon, winged nocturnal creatures, and an exaggerated yet cropped foreground prospective. Smith's flower reminds me of some of the leafy vegetation in Utamaro's Picture Book of Insects.

Moon, Flower and Hawk Moth (1917) by Alice Ravenel Huger Smith

Courtesy of the Gibbes Museum of Art

(colored woodblock print)

Bats and Moon (c. 1830s) by Katsushika Hokusai

Courtesy of the Gibbes Museum of Art (from the Collection of Motte Alston Read)

(colored woodblock print)

Horsefly and Green Caterpillar (1788) from the

Picture Book of Insects (Ehon mushi erami) by Kitagawa Utamaro

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

(colored woodblock print)

Smith's "Mossy Tree" print features one of Smith's favorite subjects, cypress trees with Spanish moss. This motif would reappear in many of her later watercolors and in at least two of her etchings. This print shows her mastery of the technique of bokashi (hand-application of a gradation of ink to achieve a variation in color from dark to light). It also appears to be her first print bearing her chop - a red diamond bearing a stylized Chinese depiction of her initials.

Mossy Tree (1918) by Alice Ravenel Huger Smith

ex-Personal Collection

(colored woodblock print)

Moss in the Wind (1925) by Alice Ravenel Huger Smith

Courtesy of the Gibbes Museum of Art

(watercolor)

The Mystic Cypress (c. 1930s?) by Alice Ravenel Huger Smith

Courtesy of the Johnson Collection

(watercolor)With "Mossy Tree," one sees Smith making the transition from nature prints to landscapes, a genre she would again explore in "Moonlight on Cooper River." Realism gives way to Impressionism, light, tone, and mood become more important than mere photographic detail. Smith's color palette is not unlike that found in shin hanga landscape prints by Fukyo and Kawase Hasui.

Moonlight on Cooper River (c. 1919) by Alice Ravenel Huger Smith

Courtesy of the Gibbes Museum of Art

(colored woodblock print)

Evening By The Water’s Edge (c. 1921) by Yanagihara Fukyo

Courtesy of Hotei Japanese Prints

(colored woodblock print)

Moon at Magome (1930) by Kawase Hasui

Courtesy of Gallery Sobi

(colored woodblock print)

Dusk at Ushibori (1930) by Kawase Hasui

Courtesy of Castle Fine Arts

(colored woodblock print)

Smith's final print was "Cotton Picker at Twilight," arguably more a figurative portrait than a landscape. Both the vertical shape of this print and its subject matter remind me of the peasant mitsugiri prints of Takahashi Hiroaki (Shotei). If anything, this print is more Japanese in spirit than any tourist print that Hiroaki ever designed.

Cotton Picker at Twilight (c. 1919) by Alice Ravenel Huger Smith

Courtesy of the Gibbes Museum of Art

(colored woodblock print)

Twilight (c. 1920s) by Takahasi Hiroaki (Shotei)

Left: Personal Collection (pigment on silk)

Right: Courtesy of Shotei.com (colored woodblock print)

Right: Courtesy of Shotei.com (colored woodblock print)

Why Smith stopped making woodblock prints is not entirely clear. It certainly wasn't because she had any reason to be disappointed in the results. Four of her five* prints were exhibited at the Chicago Society of Etchers exhibition held at the Art Institute of Chicago in April 1919 and were very well-received. They were particularly admired by Frederick Gookin, the Buckingham Curator of Japanese Prints at the Art Institute of Chicago. She would later say that the death of Motte Alston Read in 1920 made it easier for her to give up the medium. Like many Western printmakers both before and after her, Smith also probably found woodblock printmaking a laborious and time-consuming profession that was not particularly lucrative. (Smith would also give Elizabeth O'Neill Verner training in woodblock carving and printing. Verner, however, never achieved Smith's level of proficiency in that medium and concentrated instead on making etchings.) But the predominant reason why Smith abandoned woodblock prints seems to be that she found her artistic bliss working in the medium of watercolor and was lucky enough to have her talent in that medium recognized and appreciated by the art-buying public during her own lifetime.

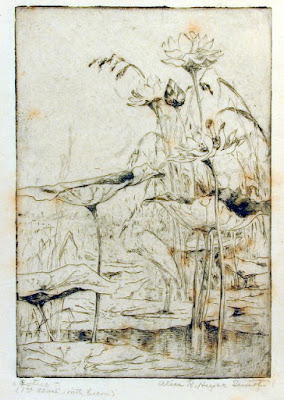

Lotus with Heron (1925) by Alice Ravenel Huger Smith

Courtesy of the Gibbes Museum of Art

(first state etching)

Other than a short stint making etchings during the 1923-1925 time period, Smith would spend the rest of her life painting watercolors. Her Charleston and Lowcountry scenes may depict innately Southern subject matter, but a Japanese aesthetic would continue to be responsible for informing her use of color and tone in such scenes. To my eyes, they seem more authentically Japanese than the soft, misty watercolors of contemporaneous Japanese watercolor artists like Ito Yuhan. Still, a woodblock print collector such as myself can only regret that she abandoned woodblock prints so early on, leaving us with only a handful of rare designs. As it is, for an artist with virtually no formal art training of any kind to master the woodblock print medium on her own and produce works of such high caliber is nothing short of astonishing. Had she continued in the medium, she undoubtedly would have become one of the foremost woodblock printmakers outside of Japan during the first half of the 20th century.

The Reserve in Summer (c. 1935) from the series

A Carolina Rice Plantation of the Fifties by Alice Ravenel Huger Smith

Courtesy of the Gibbes Museum of Art

(colored woodblock print)

Deep Water (c. 1930) by Alice Ravenel Huger Smith

Courtesy of the Gibbes Museum of Art

(watercolor)

The Reserve in Winter (c. 1935) by Alice Ravenel Huger Smith

from the series A Carolina Rice Plantation of the Fifties

Courtesy of the Gibbes Museum of Art

(watercolor)

Moon in the Mist (c. 1930s?) by Alice Ravenel Huger Smith

Courtesy of the Johnson Collection

(watercolor)

*In Japonisme Comes To America, Julia Meech states that Smith made no more than eight prints by 1924. This number appears to be due to the fact that Smith's woodblock prints are frequently assigned alternate titles and/or exist in variant color states. The five basic designs discussed above, however, are the only ones I have encountered unless one counts her early work printing from ukiyo-e blocks. Nonetheless, I welcome the chance to be proved wrong and encourage readers to let me know about any other woodblock prints made by this extraordinary artist.

Portrait of Alice Ravenel Huger Smith (c. 1930s?) by Alicia Rhett

Courtesy of Deesign

(painting)

For more information on Smith, I recommend "Alice Ravenel Huger Smith: An Artist, A Place and a Time" (Carolina Art Association 1993) by Martha R. Severens.

If a comment box does not appear below, click on this link instead: http://easternimp.blogspot.com/2017/02/the-charleston-renaissance-part-1.html

I have something interesting and need to know what they are. They are 4 book like, hand stiched, paintings, 7 paintings in each that are dated march of 1917 and the name motte Alston read is on them. Please contact me and I can send some pictures

ReplyDeleteYou didn't leave any contact information. My e-mail address is above at the upper right column.

ReplyDeleteI'm so sorry. I'm almost positive that they are hers. Please send me an email asap. lindsay92806@gmail.com

DeleteAnyway to know how many paintings she made? Thank you for sharing this information.

ReplyDeleteSmith was primarily a painter. She would have made hundreds of paintings, maybe even close to thousand over the course of her lifetime.

ReplyDeleteI stumbled across a Kakunen print (Carmel Cottage) about 15 years ago and bought it for a song. As I live in Charleston, I became entranced with AHR Smith's work only a few years back. Thanks so much for your detailed information on both of them. It is good to know that my enthusiasm for their work is shared! It is amazing that Alice Smith was self-taught and not a great traveler, yet was so stellar at her work....

ReplyDeleteSmith's woodblock prints, though rare and not well known, are indeed treasures.

Delete